Axolotl Health and Pathology: A Guide to Common Ailments and Therapeutics

The unique physiology of Ambystoma mexicanum—specifically its permeable skin and external gills—makes it highly susceptible to environmental pathogens and chemical toxicity. Maintaining optimal axolotl water chemistry is the first line of defense, but when biological equilibrium fails, rapid intervention is required. This guide explores the pathology of common urodele diseases and safe first-aid protocols.

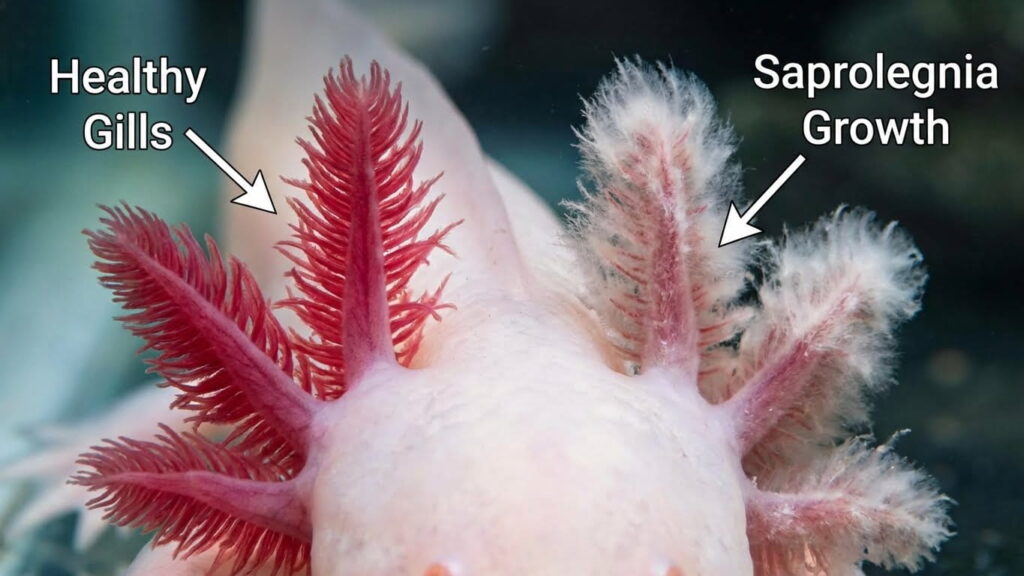

1. Saprolegniasis (Fungal Infections)

The most frequent ailment in captive axolotls is a fungal infection, typically caused by the water mold Saprolegnia. It appears as white, cotton-like tufts on the gills or skin.

- Etiology: Often triggered by high water temperatures or organic waste buildup.

- The “Tea Bath” Protocol: A localized treatment using black tea (non-flavored). The tannins in tea act as a mild astringent, soothing the skin and tightening the pores to prevent fungal hyphae from spreading.

- Scientific Resource: For detailed diagnostic imagery, consult the Merck Veterinary Manual on Amphibian Diseases.

2. Gastric Impaction and Floating Issues

Because axolotls are suction feeders, they often ingest substrate (gravel) or air, leading to gastrointestinal distress.

- Impaction: Ingesting stones larger than their mouth can cause a fatal blockage. This is why bare-bottom tanks or fine sand are critical for Ambystoma mexicanum health requirements.

- Air Gulping: Occasionally, an axolotl may float due to trapped gas. While sometimes harmless, persistent floating can indicate nutritional deficiencies or internal bacterial infections.

3. Chemical Toxicity: Ammonia and Chlorine Burns

If the nitrogen cycle in your tank crashes, the resulting spike in toxins causes “chemical burns.”

- Symptoms: Curled gill stalks, shedding skin (slime coat peeling), and lethargy.

- Emergency Response: Immediate 50% water change using a high-quality conditioner. Ensure your setup mimics the wild habitat of Lake Xochimilco to reduce environmental stress.

4. The Pharmacological “No-Go” List

The axolotl’s semi-permeable skin absorbs chemicals directly into the bloodstream. Many common fish medications are lethal to amphibians.

Toxic Substances to Avoid:

- Iodine: Can trigger unwanted metamorphosis, which is physically devastating for a neotenic species.

- Copper (Cu): Highly toxic to the branchial arches (gills).

- Malachite Green: Often found in “Ich” treatments; it is carcinogenic and lethal to axolotls.

For a comprehensive list of safe vs. unsafe medications, refer to the community-verified database at Axolotl.org Treatment Protocols

5. First Aid: The “Fridging” Technique

“Fridging” involves placing the axolotl in a tub of dechlorinated water inside a refrigerator (set to 5°C–8°C).

- Mechanism: The cold temperature slows the animal’s metabolism, allowing its immune system to focus entirely on fighting infection or passing an impaction.

- Note: This is a serious medical intervention and should only be used when metabolic stress in axolotls becomes life-threatening.